A New Direction

Doing research reviews for a bit

Hello everyone! As part of the new year, I am going to change course for a little while. For the next few weeks (or months), I am going to post brief summaries of research related to use-of-force and police tactics. I am hopeful that this will help what I consider to be useful research make its way into practitioners’ hands. The first several posts will feature research that was conducted by ALERRT. I am still working on other projects and interested in other things, so other things will occasionally pop-up.

The first review is of a small book we did awhile ago. This book discusses two research issues. I will split the review and deal with each issue in a separate post.

The Publication

Evaluating Police Tactics: An Empirical Assessment of Room Entry Techniques by J. P. Blair and M. H. Martaindale. Published by Routledge in 2014.

What is the Issue?

There has been an argument in tactical policing for decades about what is the best way to enter a room that might have a hostile suspect in it. In this book, they look at two major issues regarding room entry with a focus on room entry during active attacks. This post reviews their research on the first issue.

The first issue dealt with in the book is whether you should perform a threshold evaluation (e.g. slice the pie) before entering a room or go directly into the room. The threshold evaluation involves moving from one side of the door to the other without going into the room so that the officer can see as much as possible from the outside before entering the room. In the direct entry, the officers just go straight into the room. Proponents of directly entering the room believe that this gives you the best chance to surprise and overwhelm the suspect. Proponents of threshold evaluation argue that it allows the officers to take the larger problem of dealing with everything in the room at once and break it into a series of smaller problems that can be dealt with one at a time. They also argue that this is especially important when dealing with active attacks because the officers who respond will generally be less skilled than the tactical (SWAT) officers that originally developed the direct entry techniques.

How Did They Look at It?

The general concept of the study was to simulate a team of officers responding to an active shooter event. The participants were 199 students in ALERRT training classes. These participants self-selected into groups of 3 or 4 and then each of these groups was randomly assigned to either the threshold evaluation condition or the direct entry condition. Following assignment to a condition, each group was shown by an ALERRT instructor how to correctly perform the entry technique and then allowed to practice the technique as a team 5 times with the instructor giving feedback about each practice run (participants had already seen both techniques as part of the training class).

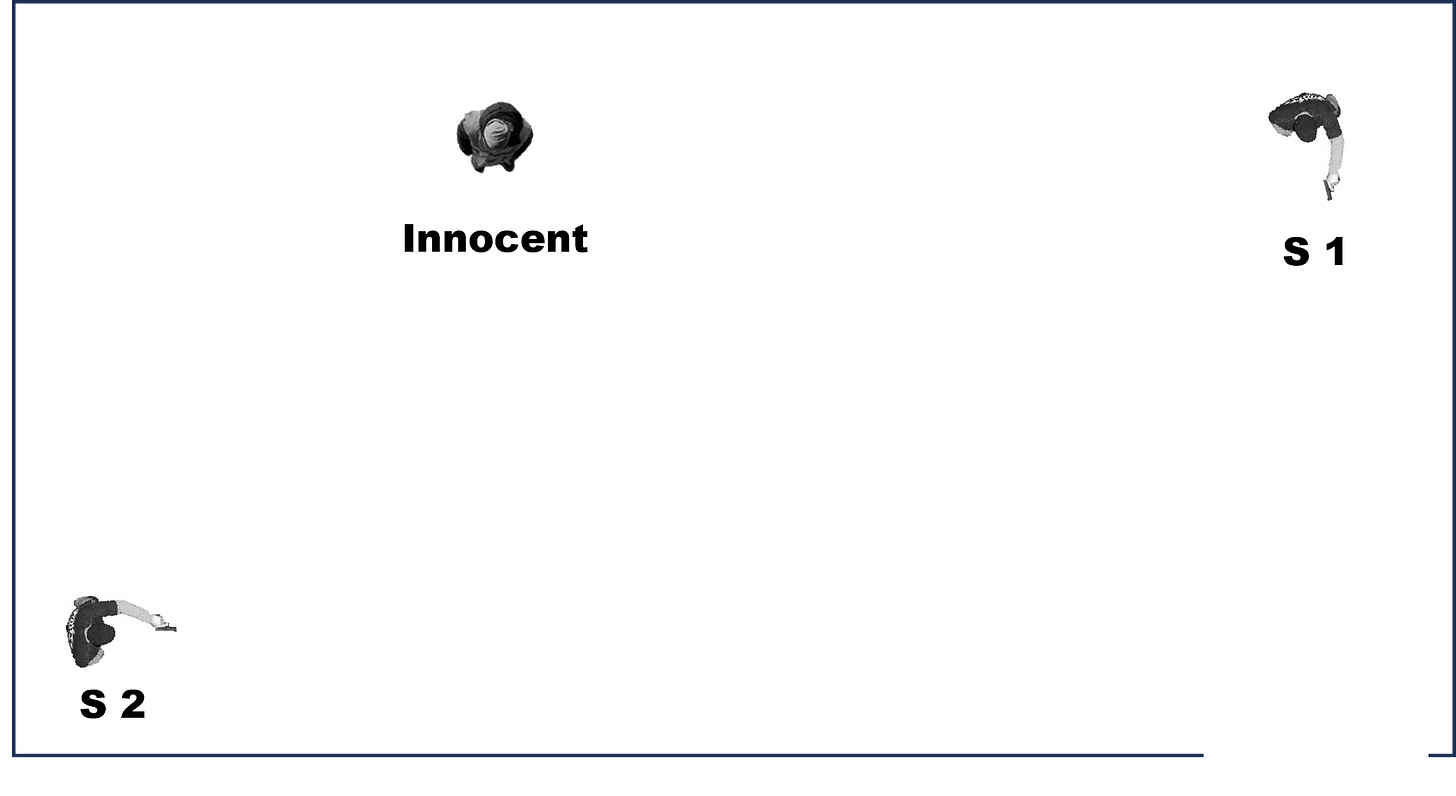

After practice was completed, the participants were introduced to the experimental task. Participants were given simunition pistols and protective equipment. After donning the equipment, they were told that they were the first responding group of officers to an active shooter event. They had received a call that shots had been fired at a school. The experimenter indicated the direction that the officers should first move in and that the officers should start responding when they heard gunfire. The scenario was declared hot and a role-player suspect began firing a blank gun. The suspect was in a room that was laid out like the illustration below. The first suspect was standing directly across from the door in the room. This suspect was the one firing the blank gun and was immediately visible as officers approached the room. Suspect two was in the hard corner and could not be seen until the participants entered the room. The innocent suspect stood in the room with his or her hands up and was included to ensure that officers were assessing threats and not simply shooting everyone in the room. Once participants had successfully dealt with (shot) both suspects, the scenario ended.

What Did They Find?

The experimenters looked at 4 primary outcome measures. The first was exposure time. This was defined as the amount of time that passed between when any part of the first officer to enter the room’s body crossed the threshold and when any entering officer detected and fired at the second suspect. This was designed to represent how long the second shooter would have been able to fire at the officers before they returned fire (In the study the second suspect began firing about a second after the officers entered the room). The average exposure time in the threshold condition was 1.2 seconds. In the direct entry condition, it was 2.7 seconds. That difference was large and statistically significant. It took over twice as long on average for officers in the direct entry condition to deal with the second suspect!

The second outcome measure was stalling in the door. During a room entry, it is important that each officer moves quickly through the door so that the entire team can get into the room. If the first officer in a group paused in the doorway or completely stopped, this was coded as a stall. None of the participants in the threshold group stalled in the doorway. In the direct entry condition, 18% of the groups stalled in the doorway. This again was a large and statically significant finding.

The third outcome was arc of fire violations. Entering a room with a team is always a somewhat chaotic process and officers move to many different places. It is important that when they shoot at suspects officers do so in a way that does not injure other officers or innocent people. An arc of fire violation represents an officer shooting at a suspect when someone who he does not intend to shoot is potentially in the way of the shot (between the officer and the suspect) or in a position that if the shot misses the suspect it could hit the unintended person (behind the suspect). In this study, all the arc of fire violations always involved another officer being between the shooting officer and the suspect. There were arc of fire violations in 12% of the threshold entries and 59% of the direct entries. That difference was very large and statistically significant. There were 4 times the number of arc of fire violations in the direct entry!

The last thing they looked at was whether the groups shot at the innocent person. This occurred in about 25% of the runs overall (although no one hit the innocent person). There were more shots at the innocent person in the threshold entries than the direct, but the difference was not statistically significant. This meant that the difference may have been due to chance variation.

So What?

This study shows that room entries are very complex situations that can be very difficult for officers to deal with. It also shows a method to help the officers manage this complexity. Performing a threshold evaluation allows officers to take a large and difficult to manage problem and break it into manageable pieces.

In the next post, I’ll talk about what they found in regarding the second issue - which way officers should go when entering the room.