Liveliness

This post draws heavily on Ecological Dynamics and the Constraints Led Approach (CLA) frameworks. As such, it is a bit jargony. These links (EcoD, CLA) give a brief overview of the main concepts if you are not familiar with them.

In many of the skills acquisition discussions that I have been listening to there has been talk about the need for “liveliness” if training is going to be effective. Josh Peacock’s definition of liveliness is ‘unscripted and uncooperative activity”. I am going to change this language a little bit. I am going to call unscripted “degrees of freedom” and uncooperative “resistance”.

Now let’s talk about resistance and degrees of freedom from an EcoD approach. When we are training people, we are trying to get them to attune to specifying information (signals that inform decision making) in the environment so that they can identify and utilize affordances (opportunities for action). Why does liveliness seem work for this? I think it can be summed up pretty easily. To perform in the “real world” the trainee must be able to spot opportunities for action (affordances) and self-organize to act (utilize affordances). The degrees of freedom aspect of liveliness means that the trainee is learning to identify when and how to produce some effect. That is the unscripted nature of the practice teaches the trainee to detect and utilize affordances, and the resistance aspect is needed to cause the training partner to present authentic affordances for the trainee to detect.

Continuum

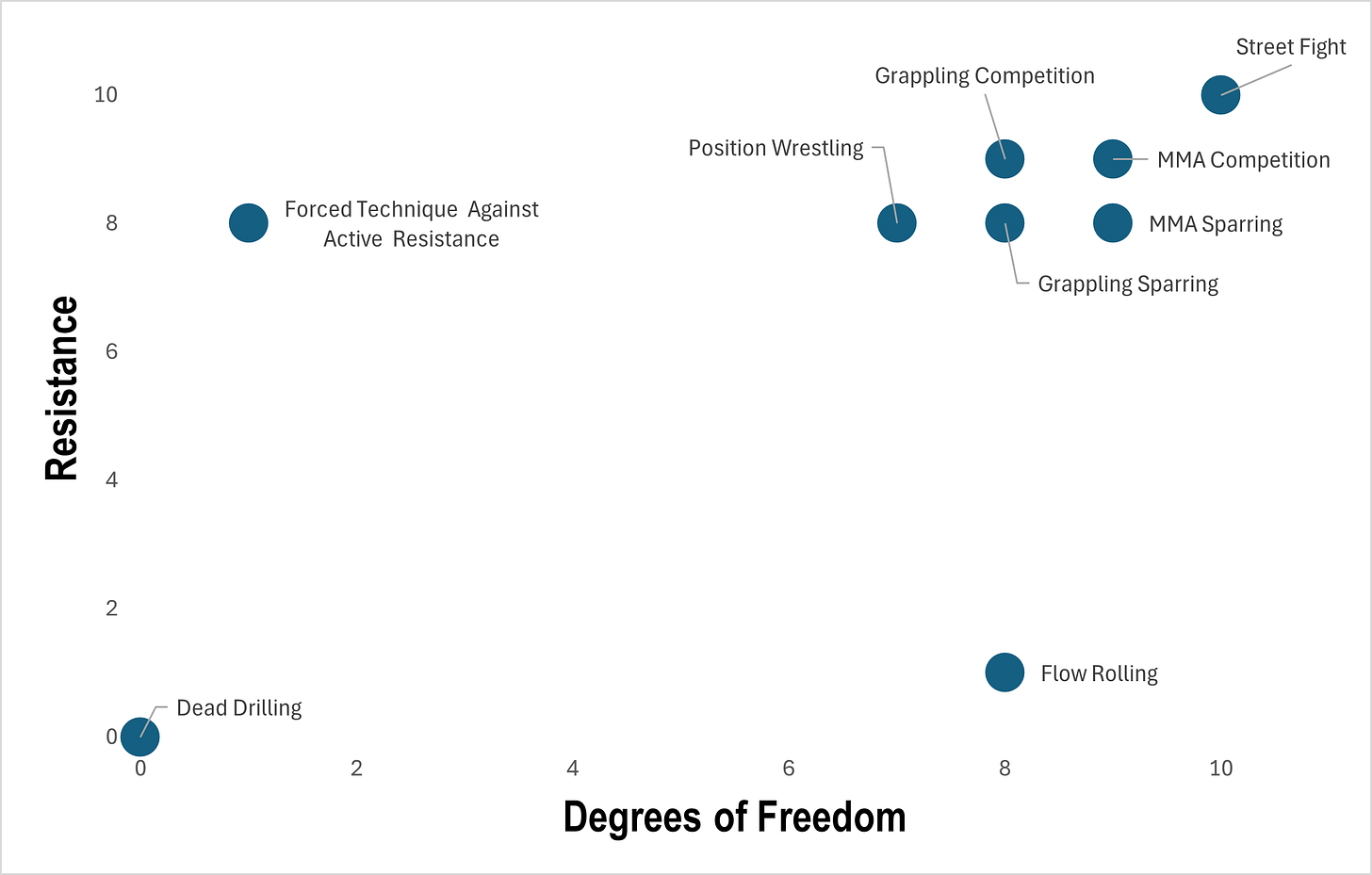

Implied in the discussions that I have heard is that there is a distinct jump from dead practice to liveliness, but once that jump is made, different activities can be more or less lively. So, there is a continuum of liveliness. Below is my attempt to map this continuum. Resistance is on the Y axis and degrees of freedom is on the X. In the top right corner, I put a street fight. It is maximum resistance. Your opponent is, at the very least, trying to kick your ass and might be trying to murder you. There are no rules. Your opponent can literally hit you with the kitchen sink. Just under that, I put an MMA competition. MMA has the least restrictive rule set but still has rules, and a serious competition fight is going to produce a level of resistance just under the street fight. Next to that, we have a grappling competition (of course it could be any other martial arts competition). The rule sets are going to be more restrictive than MMA, but the competition aspect is going to produce a lot of resistance. Then we drop down to in-class sparring. The intensity is less because it is just in class (although we all know that some students want to fight to the death), and movement is constrained by the rule set you are using. I placed position wrestling to the left of in-class sparring because the students are being constrained to starting in a particular position. Then we drop down to the lower left corner and have dead drilling. There is no resistance. Your partner is just a dummy. There is also no freedom of movement because you are trying to execute a technique in the exact way you have been shown.

I also tried to think of activities that would fall in the top left and bottom right corners. On the top left I came up with executing a single technique against high resistance. That is the trainee can only do one thing and his partner is trying his best to stop it. For example, the trainee can only try to pass using a knee cut and their partner is trying their best to stop it. On the bottom right, I came up with flow rolling. You are free to do whatever you want within the rule set and your partner is giving very low resistance.

Before I move on, I want to make a couple of points. First, obviously any particular activity can be moved some on the chart by adjusting the freedom of the trainee to act or changing the resistance that is offered. Second, I want to point out that dead drilling is the only activity here where the trainee’s partner is not learning anything. In all the other activities, the partner is at least doing something that may help them get better.

Constraints Led Approach

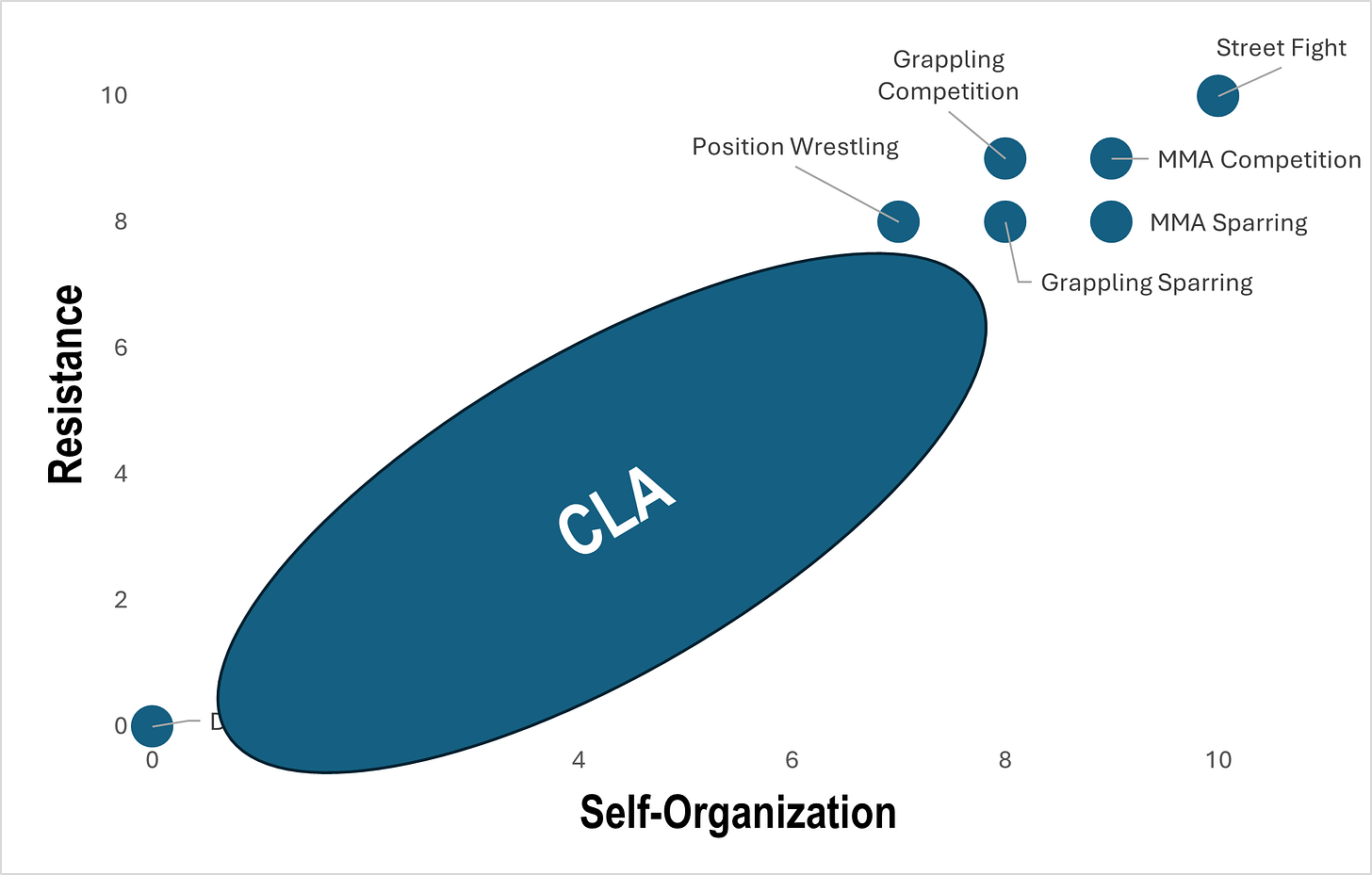

You’ll notice that there is a huge hole in the middle of the chart. To me this is where CLA nicely fits. It provides a way to move the learner from a low level of skill to a higher level where they can handle more open sparring. Here I will talk about using constraints to adjust both resistance and degrees of freedom.

The relationship between constraints and degrees of freedom is obvious. The tighter the constraints I put on a task (and most of the constraints I’ve heard people talk about in martial arts training are task constraints), the less free it is. If I create a hand-fighting game, the trainees are free to self-organize their hand-fighting, but they are limited to hand-fighting so the activity would fall more to the left on the degrees of freedom axis. As I expand the hand-fighting (say I add using the hand-fighting to get under or behind the elbows and connect with your opponent’s center), the task moves to the right on the degrees of freedom axis. This goes all the way up to open sparring where there are basically no task constraints other than the general rule set.

The relationship between constraints and resistance is a little trickier. Obviously, I can constrain the task by telling the partner to give 50% resistance. But as Greg Souders has pointed out, this is a vague constraint that is difficult to consistently implement. How do I know I am going 50% and not 52% or 60%? Also, some people’s 50% is going to be a lot more than others. Greg additionally argues that this type of instruction can produce false signals where the partner is doing things that he would not do if he was really trying. Instead, Greg uses regular task constraints on the trainee’s partner to control resistance. If practicing stand-ups, constraining the partner so that he cannot lock his hands significantly reduces resistance for the trainee. Notice that this reduces resistance by constraining the freedom of movement of the partner. This suggests that resistance is at least somewhat correlated with your partner’s freedom of movement.

Now I am going to step out on a bit of a limb. Notice in the chart above, that except for forced technique against resistance and flow rolling, all the tasks fall roughly on a line going from the bottom left corner to the upper right. This suggests to me that resistance and degrees of freedom are correlated with each other for most standard tasks that people use to train (for stats nerds a linear trend line in the chart with forced technique and flow rolling excluded explains about 96% of the variance). Here is where I get crazy. This suggests to me that effective CLA tasks should be close to that line. The ability of the trainee to organize their movement must be balanced with the resistance of the partner. This is depicted by the CLA oval (or ellipsoid if you want to be fancy) on the chart below.

Why?

Lets start with the idea of a challenge point. People learn better when they are doing something that is challenging, but not overwhelming. Rob Gray has argued that a 70% success rate is a good challenge point (for more on challenge points see this Trainers Bullpen podcast with Dr. Logan Markwell). It suggests that the task is not too easy, because the trainee fails sometimes, and yet it is not so difficult that they cannot pick up specifying information. If they are too much below that, the amount of information flowing to the participant might be overwhelming them (think drinking from a fire hose). If the trainee is succeeding all the time, they are not learning anything.

If the trainee is not at the challenge point, there are a couple of ways to address this. Let’s assume the trainee is not succeeding most of the time. We can either reduce the degrees of freedom for the trainee (e.g. make what he is trying to achieve simpler) or we can reduce the resistance on the part of the partner. Take the classic arm bar from mount where the trainee pivots off his partner’s chest and ends up with both legs over the partner. If the trainee can’t get from mount to the finished arm bar, you can have them start closer to the finish. Perhaps the trainee has both legs over the partner and the partner is on his back with his hands locked. This makes the task easier for the trainee.

The other way to go is to constrain the partner. Again, if we just give a constraint like “go 50%” this is imprecise and can give false signals. Instead, we can constrain what the partner can do. In the arm bar example, maybe you can tell them that they can’t lock their hands. This makes resisting much harder for the partner.

Interestingly, I think this works a little differently if the trainee is having too easy a time. Obviously, we can make the task harder for the trainee by starting him in a more difficult position (for the armbar, maybe he is not in mount yet). We could also constrain away options that the trainee likes to use, but increasing the resistance on the part of the partner is going to take a different form. It might require watching what is occurring and then helping the partner understand why the trainee is succeeding so that the partner can come up with another strategy to produce more resistance.

A Unified Model

As the trainee’s understanding of how to control and utilize the degrees of freedom in their environment gets better, they can handle more and more resistance. Thus, trainees start in the lower left side of the ellipsoid and, as they grow in skill, they move toward the upper right side. Ultimately, this allows CLA to extend all the way up to open sparring. Open sparring is not normally considered CLA because you are not adding specific constraints designed to focus the attention of the trainee to afford learning. But under this framework, open sparring is just a high degrees of freedom and high resistance task that is appropriate for more skilled people. It is always constrained by the specific rule set and you can add other constraints to focus on particular things. For example, a no guard pulling constraint will force the trainee to focus on his takedown game. You can easily imagine constraining open sparring to the point where the difference between CLA and sparring becomes quite blurry. Taking this approach provides a single framework where all practice activities are classified by the degrees of freedom allowed and the resistance encountered.

And yes, this model goes all the way down to dead drilling. I don’t think dead drilling is very useful because I do not think it can help the trainee learn to detect specifying information or organize to use that information. That being said, if a coach or trainee really wants to do some dead drilling, its their practice time and they can do what they want with it. Maybe dead drilling is useful to get some basic idea about how to move in a particular way. But the lack of resistance means that we are not creating real affordances and the lack of options means that we are not requiring much self-organization. This is why almost no one goes from the traditional technique practice in class to hitting the technique in live rolling. So if coaches insist on dead drilling, this model suggests that it is used only at the very beginning with very low skill athletes. It is also interesting to note that there are coaches who have shown that athletes can compete at high levels in combat sports without ever being trained using dead drilling (look up Greg Souders and Scott Sievewright if you are interested). I am unaware of any coaches who have demonstrated that an athlete can compete without using practice activities that are lively (e.g. sparring). Finally, as I pointed out before, dead drilling only allows one person to practice. All the other activities I discussed allow both sides to practice.

Anyway, I hope you find this useful. Please let me know what you think.