Publication

Blake, D., Suss, J., Wolfe, D., & Arsal, G. (2023). ‘Curb sitting’: An evidence-based policing practice or an officer safety myth? Police Practice and Research, 24(1), 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2022.2057982

What Was the Issue?

A variety of tactics have been developed to give officers more time to respond when they are attacked. One of these is commonly called curb sitting. This involves having suspects sit on the curb of a street with their legs outstretched. It is believed that having suspects sit in this position will slow them down and give officers more time to respond if the suspect were to attack or try to run. This paper examines whether this tactic actually slows suspects.

How Did They Look at It?

The researchers conducted two studies. In the first, 43 law enforcement students were recruited as participants. Each participant sat on a curb with a table 5 feet from the participant. On the table was an impact pad with a timer attached to it. When a tone sounded the participants were instructed to jump up and hit the pad as fast as possible. Each participant completed 9 trials. Three trials with their legs extended and crossed, three with their legs extended and their ankles uncrossed, and three with their knees pulled up under themselves and ankles crossed. These were all completed in a fixed order.

In the second study, the researchers recruited 105 law enforcement students as participants. These participants played the role of police officers. They stood in an interview stance at 4 fixed distances (3, 4, 5, and 6 feet) from a table with the same target pad on it from the first study. When the timer sounded, they tried to hit the pad as fast as possible. Each participant did four trials (one at each distance).

What Did They Find?

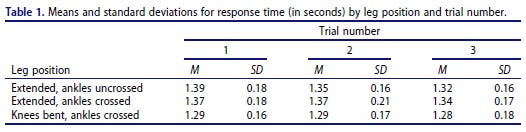

The results from the first study are presented in the table below. As you can see, it took anywhere from .04 to .10 seconds longer for the participants in the legs out conditions to get up and hit the pad than it took participants in the knees bent condition. This difference was statistically significant and suggested that having legs extended had a moderate impact on speed. The difference in the legs extended ankles crossed/uncrossed conditions was not statistically significant.

The response times from the second study are presented below. Unsurprisingly, participants took longer to reach the target as it got farther away.

Finally, they compared the time it took participants to cross 5 feet from standing in study 2 with the time it took participants in the legs extended conditions in study 1 to cross five feet. On average it took participants about 1/3 of a second longer to cross 5 feet when starting from sitting in the legs extended position than it did to cross 5 feet in the standing position. This difference was statistically significant and suggested a large effect for standing.

So What?

The results here may seem obvious. Of course, it takes longer to cross a distance if you must start from sitting with your legs extended in front of you than if you are standing! Yet despite this obviousness, the curb sitting tactic has been challenged in court. This study provides important empirical validation that allows officers to claim that it is an evidence-based tactic. The fact that so obvious a tactic has been challenged also highlights the importance of empirically validating the tactics that you teach to your officers. Please reach out to us if you have any tactics that you would like to see validated.

First of all, thank you so much for all the work you do. I am a huge fan. In my agency, I teach this approach for two reasons mainly: First, to ascertain the subject’s level of compliance and second, to place him/her at a position of disadvantage. This study validates what we do so thank you so much for putting it out there.

On another hand, I was not aware that the courts are challenging it, but being part of the 9th Circuit (Washington State), nothing surprises me anymore…🤣.

Thank you Dr. Blair!!