To Peek Or To Push: That Is The Question

Here is another brief study review.

Publication

Blair, J. P., Martaindale, M. H., & Sandel, W. L. (2019). Peek or push: An examination of two types of room clearing tactics for active shooter event response. Journal of Police Emergency Response. DOI: 10.1177/2158244019871052.

What is the Issue?

Entering a room is an inherently dangerous process for police officers because they must go from an area that they see and control to an area that they do not control and cannot see completely. Additionally, if there is a hostile suspect in a room, the suspect will know where the officers must enter (i.e. the doorway) and can therefore position himself to ambush the entering officer(s).

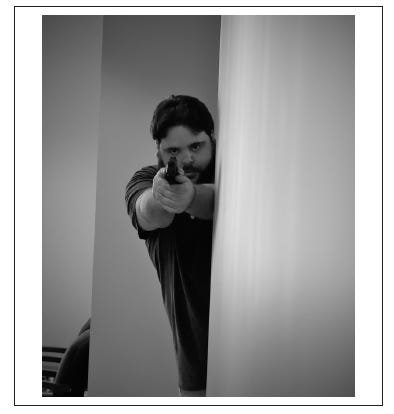

Various tactics have been developed to try and mitigate this risk. This study looks at two tactics that are commonly taught. These are referred to as the peek and the push. The peek involves the officer leaning through the doorway and exposing just his head, arms, and firearm to see the hard corner of the room (see the picture below). The push involves the officer rapidly moving through the doorway to a point of domination in the room (in this study, the entry was at a 45 degree angle off of the hard corner - entry path C in the last post).

Picture of a Peek Entry

Proponents of the peek argue that it minimizes the officer’s exposure to a suspect in the hard corner and that the wall provides the officer with some cover. Proponents of the push argue that the lateral movement provides the officer with some protection by making the suspect’s shot more difficult. They also contend that the “cover” is illusory in that most American interior construction (sheetrock and 2x4 studs) will not stop bullets. They also argue that the peek may cause the suspect to focus on shooting at the exposed body parts (head, hands, and arms) and that hits in these areas are more likely to immediately incapacitate the entering officer. Additionally, they argue that if you teach the peek, you must then also teach the push for when officers are working in a team.

How Did They Look At It?

They recruited 165 college students to play the hostile suspect in the room. Participants were placed in the hard corner of a corner fed room (the door to the room is in a corner of the room), given a training pistol loaded with one marking round, and told to ambush any officers who entered the room. The entering officer was played by a researcher. He was armed with a blank gun loaded with a single blank round. The blank was intended to induce some stress in the ambushing student without requiring they wear the full safety equipment needed to use marking rounds. Participants were randomly assigned to face either the peek or push entry. When the experiment was declared “hot” the researcher executed the assigned entry, fired his blank round, and the student fired at the researcher. The scene was declared cold and hits on the researcher were noted. The exchanges were also video recorded and coded for reaction time (how long it took the suspect to fire once any part of the researcher’s body was visible).

What Did They Find?

The participants in the peek condition successfully shot the officer 33% of the time and in the push condition they were successful 44% of the time. This difference was not statistically significant and suggested a small difference in accuracy between the groups. The hit locations of the shots are displayed below. The researchers combined the hits to the head or hands (which were directly in front of the target’s face) as head hits and all other hits were coded as other. When these were compared by entry, they found that these differences were significant with a moderate effect size. When the participants successfully shot the entering researcher, participants in the in the peek condition were more likely to shoot the researcher in the head. Average reaction time in the peek condition was .76 seconds. In the push, it was .64 seconds. This difference was not statistically significant, but did suggest a moderate difference between the entries. It took longer for the participants in the peek condition to shoot at the officer.

Hits by Entry Type

So What?

The results of this study are a mixed bag. Not much was statistically significant - meaning that we can’t have confidence that the observed differences were not the product of who got assigned to what condition. It does look like when officers get shot in the peek condition, they are moderately more likely to be shot in the face. That’s obviously bad, but in the raw data, they are also a little less likely to be shot. It also took the participants about .08 seconds longer on average to shoot at the officer in the peek condition. That is not a lot, but in a gunfight, almost a tenth of a second could be the difference between the officer getting the first shot or not. In the end, I don’t think the data provide strong enough evidence to favor one technique over the other.