Stick with me—I’ll connect this to policing, but first, let’s talk martial arts.

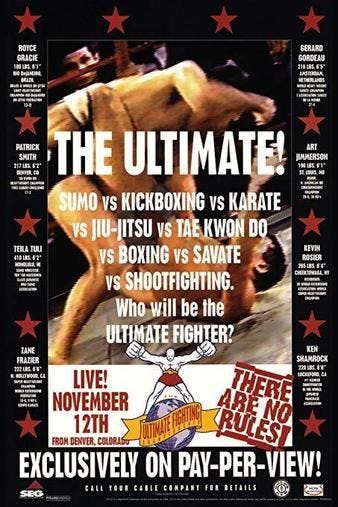

If you’re seasoned (old) and into martial arts like me, you will remember when the UFC burst onto the fighting scene. A scrawny Brazilian guy in pajamas was beating much larger and meaner looking guys from a wide variety of martial arts. For most of the world, this was our first introduction to Brazilian Jiu Jitsu (BJJ). The introduction of UFC sparked an explosion of Mixed Martial Arts (MMA), and made Brazilian Jiu Jitsu (BJJ) far more popular. BJJ looked like magic because it exposed a serious weakness in most martial artists’ games: they didn’t know how to grapple. A lot of that magic has now faded because every MMA fighter now trains grappling.

Selection Pressure

What happened here? In a nutshell, selection pressure. If you wanted to be a successful fighter, you had to be able to grapple or you were going to lose. Many people faded away. Those that stayed started working on their grappling, and now every new fighter (even if they see themselves primarily as strikers) trains grappling. The converse is also true. There was a period of time where you could be successful in MMA without training striking, but that time is gone too. Most of the striking-oriented fighters in the UFC now have good takedown defense. This means that they aren’t just going to allow a grappler to get ahold of them and drag them down. Strikers are now also much better at getting back to their feet when taken down. This means you also have to train striking to win even if you see yourself as more of a grappler (just look at Kron Gracie’s UFC matches).

Without selection pressure, you get a lot of things that people think should work, but don’t. This goes all the way down to biology. Creatures change by random mutation and then the changes either enhance fitness or not. Things that don’t work are cut out. This is selection pressure.

You can see this play out in martial arts. There has been a long division in martial arts between the “do” styles and “jitsu” styles. This is a simplification, but in general, the “do” styles focus on forms (kata) that must be performed in a prescribed way. The “jitsu” arts focus on fighting in their given rule set. If you look at “do” styles when they start out, they look like something that is close to fighting as it is imagined at the time. Over time, they tend to get more and more elaborate. Why? There is no selection pressure. If it looks cool, and if you can convince others it is cool, it gets adopted. It doesn’t matter whether it works for fighting. It might be more accurate to say that there is selection pressure, but that it selects for coolness rather than effectiveness.

In the “jitsu” arts that focus on fighting, often the opposite happens. They get simpler. Why? Selection pressure. I am going to try this awesome move. It didn’t work. Now I’m getting my head pounded in. End of trying to use that move. Innovation happens, but it is immediately stress-tested and discarded if it doesn’t work. UFC has combined ideas from a lot of martial arts, but rather than that creating a vast branching tree of things that must be mastered, selection pressure has pruned it to a much narrower set of things that work in the UFC context.

Selection Pressure in Policing

Just like in martial arts, selection pressure in policing should screen in what works and screen out what doesn’t. Is selection pressure working for policing? My short answer is “sometimes.” The longer answer is that ultimately everything is tested on the street or in real life, but how often it is tested varies dramatically. Some things get tested a lot, like empty hand control techniques, which officers use fairly frequently. So there is an opportunity to get feedback on what is working or not. Other things happen extremely rarely. Most officers will go through their entire careers and never shoot anyone. So they never really know if what they are doing in firearms training works. Some of the things that are the most critical have extremely low feedback frequencies and therefore low selection pressure.

On top of that, there is a quality of feedback problem. How many people that an officer deals with really try to fight? The answer is not many. Even in those cases where there is resistance, the suspect is usually just trying to get away. They are not really trying to hurt or kill the officer. This can create false feedback. The higher up the use-of-force continuum you go, the more of a problem this is. Most of the time, the suspect doesn’t really try to fight, so you don’t know if what you are doing really works, but it looks like it does. We did this thing 1000 times and it looked good because the suspect wasn’t resisting. But without real resistance, you don’t know if the approach actually works. You only find out your approach wasn’t effective on the 1001st time when the suspect actually fights back.

We also need to do a better job of identifying what truly works and what doesn’t. When is the last time that you saw a study that got data from the field and tried to quantify the success of empty hand techniques? How about the type of room entry used in SWAT hits? I haven’t seen it. What I have seen is a bunch of anecdotes where something did or did not work, and these seem to drive policy and training. Do a particular room entry and someone gets shot? That is a terrible type of entry! We are never doing it again! Maybe. Or maybe it was just a really tough situation that no room entry could safely navigate.

So we have a feedback problem. How can trainers create a training environment that applies realistic selection pressure? The answer is that practice needs to have a variety of characteristics, but the chief among them is liveliness. To borrow Josh Peacock’s definition, an activity is lively if it is unscripted and uncooperative. Meaning your partner is trying to stop you and they have freedom to act as they want. This can be constrained to focus on particular aspects of the situation, but it can’t be a scripted set piece. I talk a little more about this in this post. In a nutshell, training for any skill that involves succeeding against another person needs to be lively. If you want the training to transfer effectively, it must reflect the actual performance environment.

Improving Selection Pressure

In the martial arts community, a number of instructors have taken this to the point of making all practice lively. They don’t drill techniques, hit bags, or use other unlively activities. They spar (roll) all practice, every practice. They use constraints to target specific aspects of their sport, but every practice is fully unscripted and uncooperative. They are also starting to have a lot of competitive success. To see this in BJJ, check out Greg Souders. To see it in MMA/striking, see Scott Sievewright.

Let’s take traditional Jiu Jitsu training. A typical class will have 10 to 15 minutes of warmup. Some of the warmup tasks (shrimping down the mat) look kind of like movements you see in Jiu Jitsu matches. Then a series of techniques are shown. The instructor shows these techniques as a series of steps. Sometimes there can be 10 or more steps to the technique. Each technique is practiced (drilled) against no or very low resistance. Your partner is essentially a practice dummy. A good coach will link the techniques together so that they flow. This usually takes 30-40 minutes. Then, at the end of class, you spar (roll) for 10 to 15 minutes.

Now, look at how Greg Souders does his classes. He introduces a task. It takes no more than 2 minutes to explain where you are in the game and what you are trying to accomplish. He also gives your partner goals to accomplish. Then you practice achieving your objective while your partner tries to stop you and achieve theirs. In other words, you are sparring against your partner in a constrained way. In a beginner class, you do this task for 6 minutes. Then the task is changed—usually making it a little more complicated—and again explained in less than 2 minutes. Then back at it for another 6 minutes. Halfway through the class, the task is changed to deal with a different part of the game. You get a task for that area and practice it against resistance for 6 minutes, and on and on until the class is over. You are generally going to get 6 or 7 tasks in a class. That is 36 to 42 minutes of sparring! Task time also increases after the beginner class to 10 minutes per task. That gives you somewhere around 50 minutes of sparring per 1-hour class.

Even if you don’t believe in any of the theoretical background of EcoD, who do you think is going to be better at sparring(rolling)? The kid who gets 10 to 15 minutes per class or the one who gets 36 to 42? The person in Greg’s class rolls 2 to 3 times more than in a traditional class, so naturally, they will be better at it. Its also important to note that both sides of the task are learning the whole time. In the traditional class, only one side is learning during the drilling phase of practice. The other is a practice dummy.

On top of that, both participant’s in Greg’s tasks are constantly exposed to selection pressure. They are both trying to win (accomplish their task) to the best of their abilities. If you are a lot better than the other person, you either make your goal more complex or simplify the less skilled person’s task. This means that both are getting real signals about what works or does not work the whole time. This gives them a realistic idea about what happens in competition - which is exactly what they are training for.

What about Policing?

This all goes back to something that I have said many times on this substack. If you want to get good at something, practice that thing. We frankly have a lot of practice activities in law enforcement that are probably the equivalent of exercise bikes. They look kind of like what we are trying to teach officers to do, but they are missing key things that are needed to increase the likelihood that training will transfer to the real world. Hitting heavy bags, practicing restraint techniques on unresisting people, and shooting at paper targets probably all fall in the category of exercise bikes. Some of these activities have their place—you need to ensure trainees can safely operate their firearms and hit their targets before moving on to complex scenarios. What I am suggesting though is that there are probably other training activities that you could be doing that would have a much better chance of developing skills that transfer to the real world. Those activities are lively!

In short, training should involve things that look more like sparring and less like isolated set pieces or decomposed parts of a process. For example, instead of practicing empty-hand restraint techniques on a compliant partner, officers could engage in limited, unscripted scenarios where their partner actively resists. This way, officers are exposed to real-time decision-making and adaptive problem-solving, making their training more reflective of actual field conditions. This is the will add consistent selection pressure, and as we saw in martial arts, the addition of selection pressure can revolutionize a field. While I believe that there is a need for this across police training, perhaps the area where this need is most pronounced is firearms training. I will step on this third rail in the next post.

I think so. Can't wait for what's to come.

Excellent article. I commend your willingness to step on that proverbial third rail without getting zapped. Will be looking forward to the application of selection pressure and liveliness to firearms training.