Ecological Doesn't Mean Anything Goes

An example using room entries

One of the things I’ve encountered in teaching and talking about Ecological Dynamics is the idea that if we’re not showing someone “THE” way to do something, then we’re just saying, “Do whatever.” That’s just plain wrong. Ecological training isn’t scripted—but it is structured. It’s built to create problems worth solving, conditions that demand action, and feedback that comes from the environment itself. What looks like chaos from the outside is actually a carefully shaped space for developing real-world adaptability.

Being an EcoD trainer or coach isn’t lazy—in many ways, it’s harder than the traditional method. The difference is that most of the hard work happens before we ever step into the training space. We’re identifying task invariants, designing representative scenarios, setting constraints, and building meaningful perception-action loops. It’s intensive, invisible prep work, and we do it because it produces training that is more likely to transfer to the real world.

So I’m going to lay out part of why EcoD coaches do what they do—and then I’m really going to step in it and show how this approach applies to teaching room entries. (I can already hear the SWAT guys fastening their Velcro.)

Issue 1 - Even if you know what you know (which you don’t), you can’t explain it.

Most of you became trainers/coaches because you had some level of skill in something. In law enforcement its often something like - you do martial arts - you should be the defensive tactics instructor. At the surface level, it makes sense that you should know how to do something before you can teach someone to do it.

Unfortunately, knowing how to do something does not mean that you know how you do it, much less that you can explain how you do it to someone else. You know how to ride a bike, but you probably don’t know how you do it. If I press you, you’ll come up with a story that might sound good, but its probably not what you are really doing. The same is true for professional athletes. Like Michael Jordan, they Just Do It. They don’t really know how. If you don’t really know how, how can you explain it? The academic phrase for things that we know but can’t verbalize or explain is tacit knowledge. It appears that most of the knowledge that drives skillful performance is tacit. In EcoD, we like to use the terms “knowledge of” for tacit knowledge and “knowledge about” for explicit knowledge.

Then you add all the potential for misunderstood communication, and you get a very weak medium for developing skill. If you take a deep dive into the literature (which I’ll spare you here—you're welcome!), you’ll discover that verbal and visual instruction are poor substitutes for experience. The best way to learn to do something is to do it. I’m not saying that there is no value in verbal instruction or physical demonstration. I am saying you get much more out of doing whatever it is that you are trying to learn. This is called experiential learning and it is what we should be focusing on as trainers. We want trainees to experience what we know so that they can know it too.

Issue 2 - What is it that they need to experience?

This is the hard part. It requires trainers to take a really deep look at what is essential for success. What are the things that must occur in a given situation? What is always present no matter what? These are called invariants in the EcoD literature. Then, we need to carefully think through the variations in the environment, task, and performer that we need to model in our training tasks. In my experience, most trainers haven’t spent the time needed to identify the invariants of success or variants of the situation that they are trying to teach.

Below, I’ll use an EcoD approach to teaching room entries, walking through a series of carefully designed tasks that emphasize perceptual cues, movement coordination, and decision-making under pressure. The specific approach that I am using is called the Constraints-Led Approach. You can read more about it here.

Those who know something about room entries will see that the tasks I am having the students complete require me to understand not just a set of basic tactics, but the deeper things that the tactics facilitate. Things like clearing primary threat areas and then secondary, massing fire without violating the fundamental firearms safety rules, and threat discrimination. I also have to figure out how to get students to experience these things.

Room Entries

Ok - here we go!

I want to start by acknowledging that I am not an “Operator” (said in a whisper). I was never on a SWAT team or even a street cop. On my best day, I am medium speed and moderate drag. I have never been shot at or shot anyone with anything more serious than a simunition round.

That being said, a lot of the early research I did with ALERRT was about this topic and I have talked to hundreds of people - from line officers to SWAT and Special Forces Operators - who have been there and done that. I have witnessed and been part of many, as in more than I can count, as in way too many arguments about the “best way” to do room entries. I have observed thousands of entries both in training and from actual events. I have heard lots of different takes on this subject and empirically tested a bunch of them as well (see here, here, and here). At the end of the day, the only dog I have in this fight is that I want to ensure that officers have the best training possible so that they have the best chance of winning the fight and going home that night. I take that responsibility very seriously and I am always concerned (more like terrified) that I might give someone bad information that will get them killed.

Here’s how I approach room entries today. I don’t think that there is a “best” way to do them. I know - Blasphemy! Heresy! Apostasy! Sure, after the event, when we have all the facts and time in the world to think a given room entry through and we can assume perfect actions from the team, we can come up with the optimal solution, but there is no way to have the optimal solution in the moment. The best we can hope for is an entry that does a good enough job of achieving the objectives given the officers’ read of the situation at the time.

Why do I think this? There are lots of reasons, but one of the big ones comes from talking to and observing professionals. Every SWAT guy and special forces operator that I have talked to has indicated that their hits never go to plan. When I ask commanders, if I give you a diagram and indicate the starting positions of your people, can you tell me where they will be at the end? They all (and I mean every single one) say no. When I ask why, they say that the situation is too dynamic and their people are making spur-of-the-moment reads that the rest of the team is reacting to.

These are full-time teams that train constantly and include the most competent people they can find. They also operate under very tight CQB guidelines and rules (some of them have page after page of contingencies spelling out every possible scenario they can think of). They are the best at what they do. They should have less variability than any other group doing this, and yet, even they cannot predict what they will do. This is not a problem. They are not making mistakes. They are exhibiting the flexibility and adaptability needed for the task at hand.

If the task requires flexibility and adaptability, then that is what we must be training officers for. Whatever they learn has to be flexible and adaptable enough to cover the situations we are asking them to solve. It can’t be a single technique like going to the unknown, running the rabbit, or strong wall.

What Could We Do Instead?

I’ll walk you through how I think about the problem.

Objective

First, we need to know what we are trying to accomplish or our intention. I am going to define a room entry as moving from a place that we are in/control to one that we do not. The primary objective of a room entry is to take control of this new space. Now, there is a whole list of things that go into controlling that new space, but I am not going to bog the students down with it. I am going to design tasks that get them to experience the things that are needed for control. Much of this will involve experiencing a lack of control.

Room entry - Moving from a place that we control to one that we do not.

Primary intention - Take control of the new space.

Assumptions

I am going to start with some assumptions to limit the possibilities that I have to cover in this post. For the sake of brevity, I am also going to just lay them out and not argue them here (I’m happy to debate them in the comments).

The officers do a full threshold evaluation (moving from one side of the door to the other to see as much as possible) before entering the room. They deal with any problems (e.g., bad guys) they see during the threshold evaluation from the hallway. Participants have also already done some tasks involving this before they complete the room entry tasks.

They are going to commit to a full room entry - meaning their bodies are all the way inside the room - no peeks or leans.

We are going to limit the distance the participants go into the room to 2–3 steps during the initial entry.

This is not the first training activity they have done. So they know things like the fundamental firearms safety rules are always in play, how to communicate with each other, and how to mass firepower on a threat.

These reps can be done with anything from blue guns to full simunition gear. While these can be done with blue guns, the closer to force-on-force the reps are, the more likely they are to transfer to the field.

Tasks

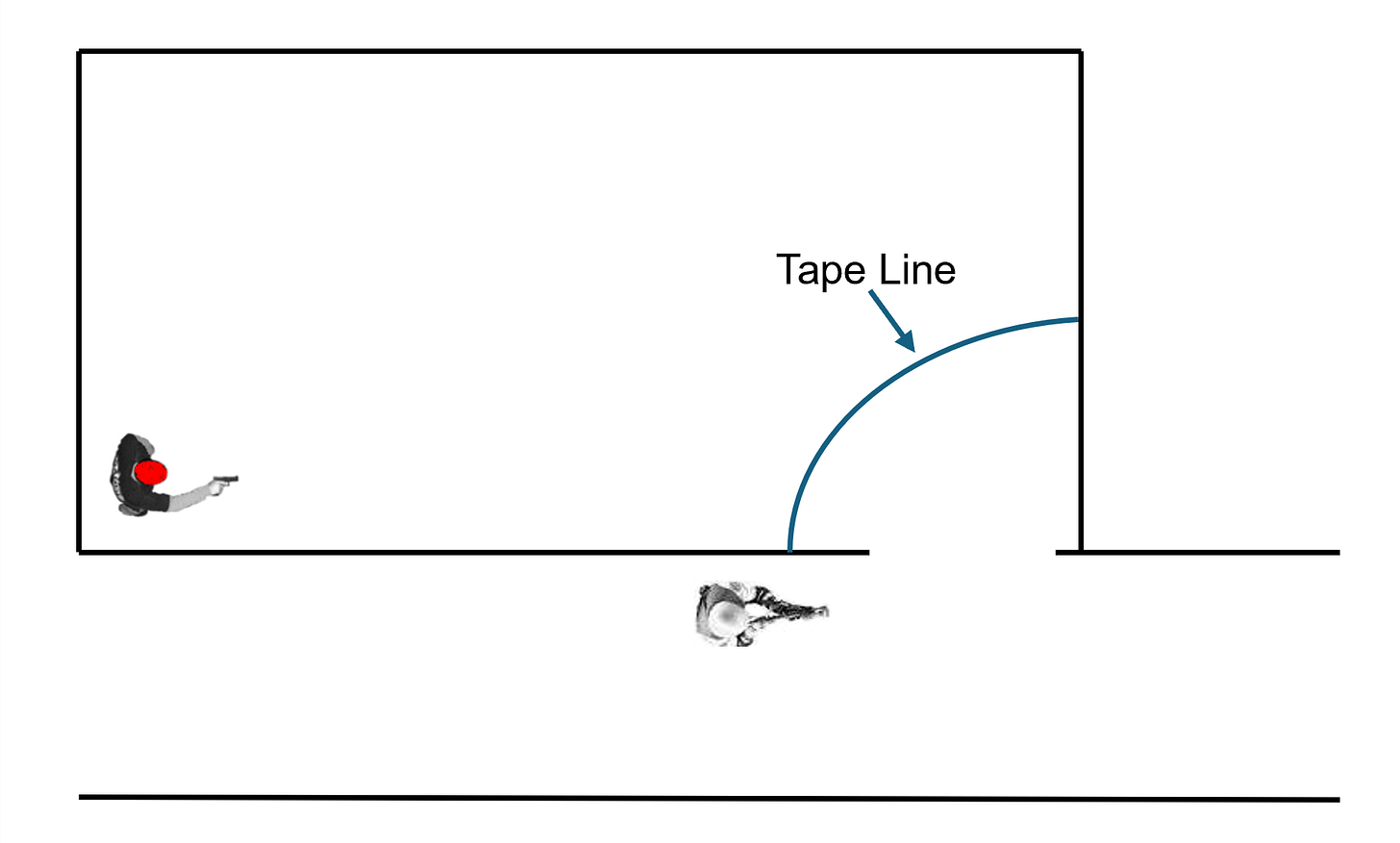

I am going to do these just for rooms where the door is in the corner (i.e. the room is corner fed) but they can easily be modified for rooms where the door is in the center. For all the initial tasks, I will put a tape semicircle about 5 feet inside of the door. There is a two-question debrief after each scenario:

Ask the officer: "Anything you can do to control the room better?"

Ask the suspect: "How could the officer have done a better job of taking control of the room?"

These tasks are fast, taking just a few seconds to complete each run, so you can do a lot of them in a very short time. This builds quick decision-making under stress and reinforces repetition as the path to skill.

Trainees always do the first run of a task as the officer and then they become the bad guy in the solo scenarios. In the two-officer scenarios, they start as the first officer in, then move to the second officer in, and then the bad guy. The instructor is the bad guy in the first run.

Task 1 - Addressing Primary Threat Area – Solo Officer

Instructions

Room Layout

This is a pretty open room. There can be furniture in it, but there should not be anything that creates an area that would require a secondary clear. Below is an example of the starting position for the officer and suspect.

Solo Officer

You are doing a room entry to take control of the room. After completing your threshold evaluation, enter the room, and take control. You must move past the tape line and then stop. You can’t move from where you stopped until you communicate.

Suspect

You must stand in the hard corner and cannot move from it. As soon as you can see the officer, you must say out loud, “I see you” and then count one one-thousand before you bring the gun up and start shooting. Go down when the officer shoots you. The instructor should have the suspect demonstrate it before starting the scenario. You want to slow the suspect down so that the officer can shoot first. As trainees get better, you can reduce the suspect’s reaction time.

The scenario starts with simulated gunfire because that is the only reason a solo officer would be making a room entry.

Explanation for the Instructor

This is designed to get the officer to perform a hasty threshold evaluation and engage an active attacker. The tape line is to get them to move the proper distance to get them out of the door and allow other people in during later tasks. Because the officer has done a threshold evaluation, there is only one primary threat area that must be addressed on entry—the hard corner on the same wall as the door. Placing the attacker in the hard corner emphasizes looking in that corner.

Variations

Change rooms or the room layout.

Make the officer enter on a different line—put a chair or other obstacle on the line they took the previous time.

Task 2 – Addressing Primary Threat Area – Two Officers

Instructions

Room Layout

Layout should be similar to Task 1—largely unobstructed to support line of sight and clean movement paths. There can be furniture in it, but there should not be anything that creates an area that would require a secondary clear.

Officers

You are doing a room entry to take control of the room. Perform a threshold evaluation, communicate, make entry, and take control of the room. You both must move past the line and then stop. Do not flag/laser your partner. You cannot move from your stop position until you communicate.

Suspect

You must stand in the hard corner and cannot move from it. As soon as you see an officer, say out loud, “I see you” and count one one-thousand before bringing the gun up and shooting. Go down when the officer shoots you.

Explanation for Instructors

This task builds on Task 1 by requiring two officers to coordinate their movement. The threat remains in the hard corner, focusing attention on how to mass firepower and avoid obstructing lanes of fire.

Variations

Change rooms or the layout.

Add obstacles on the preferred entry line.

Introduce "bad partner" runs.

Add gunfire as a driving force.

No one in the room runs.

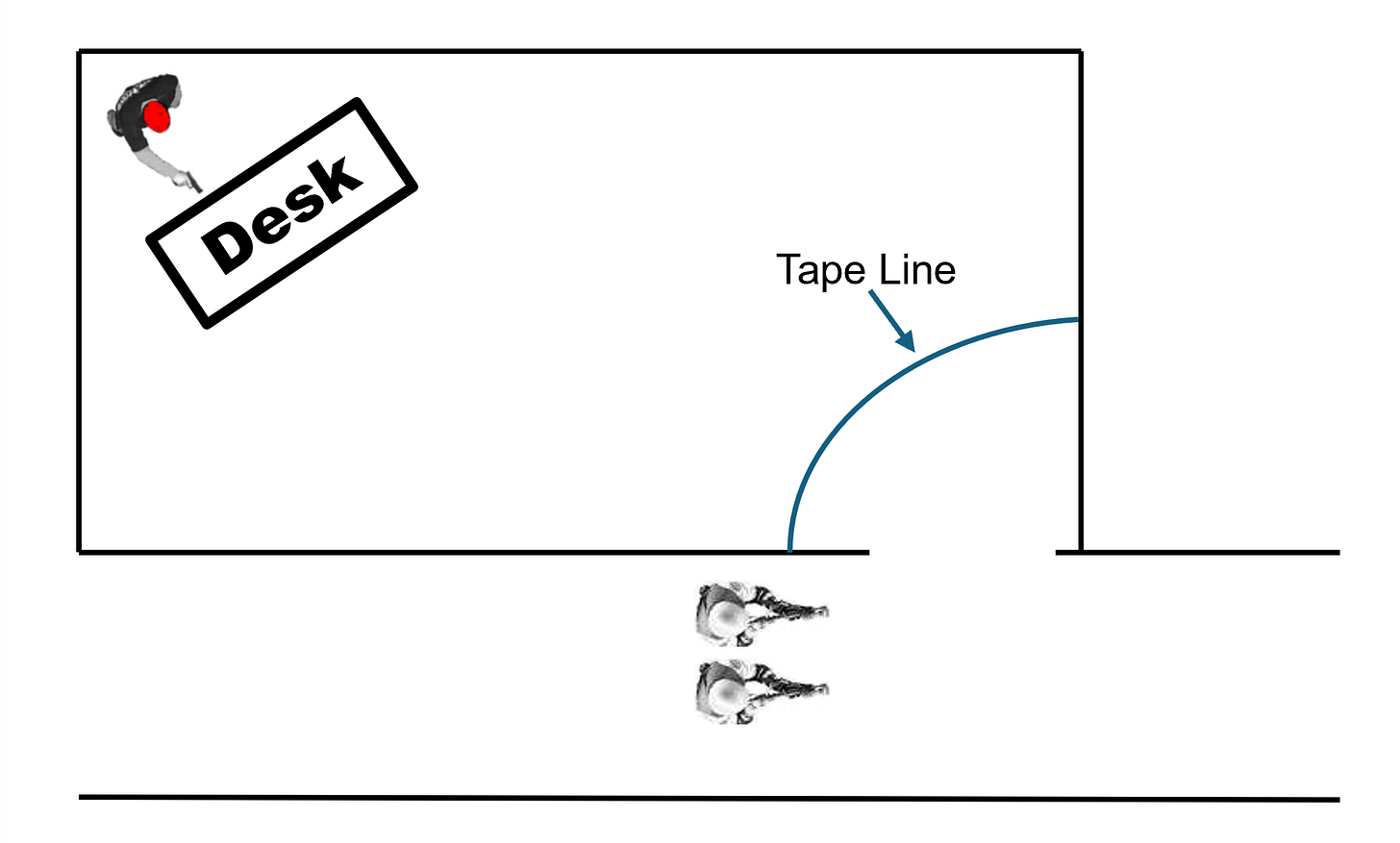

Task 3 – Addressing Secondary Threat Area – Two Officers

Instructions

Room Layout

Add a secondary threat area—something like a desk or other obstruction that creates an area that cannot be seen from the threshold. This secondary area should initially be in the same half of the room as the hard corner so that it will be visible in the officers’ peripheral vision as they address the hard corner. See image below.

Officers

You are doing a room entry to take control of the room. Perform a threshold evaluation, communicate, and enter. Move past the line and stop. Do not flag/laser your partner. Do not move again until you communicate.

Suspect

Stay behind the desk and get down low so that the officers can’t see you. When the officers enter, stand all the way up with the gun at your side and then raise it to shoot. Go down when you are shot.

Explanation for Instructors

Officers must manage both the primary and secondary threat areas. The pop-up suspect discourages tunnel vision on the primary threat. Later runs may involve no suspect, requiring officers to clear the secondary area themselves.

Variations

Change room layout so that the secondary clear area is now in the other half of the room.

Suspect waits for officers to clear the hiding place.

No suspect present.

Bad partner runs.

Add gunfire as a driver.

Task 4 – Dynamic Threat Assessment – Two Officers

Instructions

Same as above, but now the suspect may appear in the hard corner, in a secondary threat area, or not be present at all. The room always contains a secondary threat area.

Explanation

Officers must process multiple possibilities and allocate attention and positioning accordingly.

Task 5 – Unknowns in the Room

Instructions

Add role players who are not hostile. Sometimes an unknown. Sometimes a threat. Sometimes both.

Explanation

Increases complexity by requiring officers to distinguish threats from non-threats and communicate accordingly. The goal is to keep the officers guessing—and reading the room

I think these five tasks establish a solid foundation for adaptive, experience-driven learning in this critical skill area, but they are only one possible beginning. They can be adjusted to focus on any aspect of room entry. For example, if you think your people need more work on threat discrimination, put more unknown people in the tasks so that your trainees always make a threat/no threat determination.

A Few More Points

The instructor should not be doing a lot of verbal instruction during these runs. This does not mean they are silent. Most of what they say will relate to reinforcing the rules. Trainees don’t cross the tape line - Instructor says, “tape line.” One trainee flags another - Instructor yells, “Flagging!” Trainee out of position to mass fire on the suspect with his partner - Instructor says, “Mass firepower.”

I said we run these fast. I meant it. No standing around, no jibby-jabbing. You explain the rules, and then go.

Student questions? Only about the rules. After each run, we ask the two questions, reset, and roll again. The goal is one minute per rep, but don’t confuse speed with simplicity. Every rep is a decision. Every rep is a pressure moment. Every rep is an experience.

The students answer the debrief questions—not the instructor. And if someone asks, “Can I do X, Y, or Z?” the answer is: “Try it.” Or just “Yes.”

You know a lot of important things. But they’re not going to learn them from you telling them. They have to experience them. Your primary job is to design those experiences.

If they’re not making mistakes, they’re not learning.

Variation within the task is added based upon individual student performance. If the student is switched on an getting it, throw them a variation. If the student is struggling, stick with the basic task. Once all students in a group are doing a pretty good job, change the task. Once you have this down, you can do a lot of runs in a very short timeframe.

If you run a single task for an hour, you can get 58 runs in — 1 run per minute minus two minutes to explain the task. Each run is decision-rich and feedback-driven, not just mechanical repetition. If you get really good, you can go faster than that. If you have a group that is reasonably together and you are on it, you have 10 minutes of explanation for the 5 tasks and 50 runs. Now, I know there will be slippage and we won’t get the perfect 50 runs, but we will get the students to do a lot of runs. That’s a lot of decision points, a lot of pressure moments, and a lot chances to experience what works or doesn’t.

Discussion

Ok. Here I want you to take a moment and really think about what I just laid out. No I mean it, take a second before you go on.

This approach is focused on experience. We want students doing as much as we can fit in, and we want instructors talking as little as possible. To do this we have to design tasks to give the students as much direct feedback as possible. This means the student knows they are doing it right or wrong from the outcomes they are producing. If they shoot the bad guy first, they win. If the bad guy shoots them, they lose. Did I go far enough in the room? The tape shows me. Did I pick a bad spot? I know because I couldn’t mass fire on the threat (my partner was in my lane of fire). The instructor still has some things he points out like you flagged you partner and he can give the trainee nudges if they are failing (e.g. what happens if you try this instead?).

I hope you can see that we are not throwing a bad guy in the room, putting the students outside of the room, saying — “Go!”, and then accepting whatever happens. The tasks start very simple. We focus on a small sliver of the problem while keeping the context of the whole problem intact. As the students are able to handle the small problem, we increase complexity, but we are still guiding the students by constraining the task. Each task is either focusing the student on dealing with a particular part of the problem or connecting different parts after the student has experienced them separately.

These tasks provide students with the essential groundwork to solve real room entry problems because we have made them work through actual situations. They will have direct experience with many of the things that we know are important about room entries. Things like clear the hard corner first, then look at your secondary threat areas. Things like where and how they should move. We could tell them these things, but to really “know” them, the trainee must experience them. The trainee will also know a lot of tacit things that can’t be explained - only experienced. Obviously, they’re not at SWAT level. They’ll need a lot more experience to reach that proficiency, but they are already doing many things that look very SWAT like.

Now contrast this with the typical training setup. We give a lecture about room entries. The lecture covers a bunch of steps that you must complete to do a room entry and diagrams of the right way to do an entry. There is a list of does and don’ts. Then an instructor demonstrates how you perform those steps in a room that is intentionally set up to allow him to complete all the steps. The instructor watches as you copy what he told and showed you. He corrects you when you don’t do it the right way. In this practice, the focus is on getting the steps right. Once you can do the steps the right way, maybe we have you do it with a bad guy in the corner and maybe we cover some adjustments you can use if the room won’t allow the preferred method to be executed. Which training method is going to produce more skill?

Again, its not that the traditional approach has no value. It does have some. After all, its how most of us were taught. The question is how do we get the most skill acquisition out of a training session? If you believe what I laid out above, that experience is the best way to learn, which training activity gives more experience? Which one provides trainees with more access to all the tacit things you know, but can’t verbalize? I think the answer is obvious. One group is developing a feel for room entries. The other is trying to make sure they did all the steps on the checklist.

The Dream

Now imagine that we did this for an entire eight hour training day. Let's say we did an hour each on:

Exterior approaches

Interior movements

Threshold setup

Room entries

Security, Incident Command, and Medical (SIM).

Again, we are not explaining all the things that students need to memorize and think about. We are repping out tightly designed tasks. That’s 5 hours of rep time. If we can get everything tightly coordinated, that could be 250 runs during that five hours. Then lets say we use the next 2 hours to connect the different areas together. These runs will not be as fast because we are going to ask the students to do more. Things like move down the hall, do a threshold, and enter the room or do a threshold, enter the room, and do SIM. Lets say these each take 3 minutes to run. We will still have tightly designed tasks so lets say with instruction we can do 15 of these an hour. That is another 30 runs bringing our total to 280. During the last hour, we do runs where the officers put everything together from the initial call to exterior movements, entry, interior movement, threshold evaluation, room entry, and SIM. These will be slower. If we go really slow each one takes 10 minutes. That is another 6 reps (and each student would get at least one full run at a typical 6:1 student to instructor ratio). So our total is now 286 reps in the day.

No doubt — this is would be a demanding day for the trainees and instructors. However, because we are doing rotations, we are keeping the students moving and engaged, but not physically exhausting them. Take the two person tasks, students will be doing no more than 3 minutes of work and then getting 3 minutes of rest. The rest times will get longer as the tasks get longer.

Also, I am sure there would be some slippage making it difficult to get all 286 runs in, but even if we lose about a third of the reps and only get 200 done, that is still a lot of experience we’ve given the trainees.

Imagine if this was the academy and instead of jamming it all into one day, we spread it out over weeks. Now, we get sleep cycles to consolidate learning, forgetting and refreshing to strengthen neural pathways, and interleaving with other tasks. These things will all produce better skill development and retention. How much more skilled would our officers be then? We can dream, right?

As a parting thought - Clean training builds confidence. Dirty training builds competence. If your reps aren’t messy, your people aren’t ready.

Another Great Article, worth the read, re-read, study, then apply, Success and Skill Takes Time. Here is my point, many LE agencies have tactical teams (not full time) that are drawn from their regular duties as the calls require their assistance. Some agencies have full time tactical teams; some have none and draw upon their patrol shifts not only for the immediate response, but capabilities of taking immediate action if required! Every LEO agency should take the time to review these incidents. Then ask themselves how are we going to handle this situation, what are our capabilities, what are our limits, and how can we improve these concerns for a professional response, and successfull conclusion! Then the patrol shifts, on call tac teams can devote at least 40 hrs. a year or more to just this concept or more time as needed. The big boys( Delta, HRT, GSG-9, etc. have been doing this for sometime. Because Shit Happens even in Practice, eliminate that Factor. Make this type of training a priority on every exercise, success will be more achievable!!!

As usual. Great article. I contacted you years ago about the hybrid-room clearing method I was teaching that was very similar to what you abdicated. I am happy to see many of our training principles here. Build the skill and tactics to practical speed and application faster than you are comfortable with. Experiential Learning is the goal. You can. Always re-vsist skills and tactics more in isolation if they are a significant problem in the execution of the tactic. Please keep up your fa tastic and meaningful works - From a not-quite yet former operator pretending to dabble in academics.